Thursday, January 18, 2018

by ERIC ANDREW-GEE[411 Note: We’ve been saying it for a long, long time – and more and more articles like this keep coming out. But nothing changes. It only gets worse. Isn’t that a clear sign of the addictive nature of such devices? Made us do something about it. How about you?]

A decade ago, smart devices promised to change the way we think and interact, and they have – but not by making us smarter. Eric Andrew-Gee explores the growing body of scientific evidence that digital distraction is damaging our minds

SOURCE PHOTO: ISTOCKPHOTO PHOTO ILLUSTRATION: THE GLOBE AND MAIL

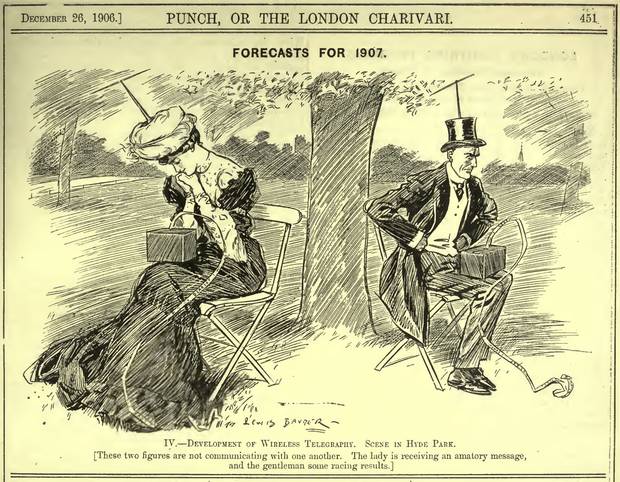

In the winter of 1906, the year San Francisco was destroyed by an earthquake and SOS became the international distress signal, Britain’s Punch magazine published a dark joke about the future of technology.

Under the headline, “Forecasts for 1907,” a black and white cartoon showed a well-dressed Edwardian couple sitting in a London park. The man and woman are turned away from each other, antennae protruding from their hats. In their laps are little black boxes, spitting out ticker tape.

A caption reads: “These two figures are not communicating with one another. The lady is receiving an amatory message, and the gentleman some racing results.”

The cartoonist was going for broad humour, but today the image looks prophetic. A century after it was published, Steve Jobs unveiled the first iPhone. Today, thanks to him, we can sit in parks and not only receive amatory messages and racing results, but summon all the world’s knowledge with a few taps of our thumbs, listen to virtually every song ever recorded and communicate instantaneously with everyone we know.

More than two billion people around the world, including three-quarters of Canadians, now have this magic at their fingertips – and it’s changing the way we do countless things, from taking photos to summoning taxis. But smartphones have also changed us – changed our natures in elemental ways, reshaping the way we think and interact. For all their many conveniences, it is here, in the way they have changed not just industries or habits but people themselves, that the joke of the cartoon has started to show its dark side.

The evidence for this goes beyond the carping of Luddites. It’s there, cold and hard, in a growing body of research by psychiatrists, neuroscientists, marketers and public health experts. What these people say – and what their research shows – is that smartphones are causing real damage to our minds and relationships, measurable in seconds shaved off the average attention span, reduced brain power, declines in work-life balance and hours less of family time.

They have impaired our ability to remember. They make it more difficult to daydream and think creatively. They make us more vulnerable to anxiety. They make parents ignore their children. And they are addictive, if not in the contested clinical sense then for all intents and purposes.

Consider this: In the first five years of the smartphone era, the proportion of Americans who said internet use interfered with their family time nearly tripled, from 11 per cent to 28 per cent. And this: Smartphone use takes about the same cognitive toll as losing a full night’s sleep. In other words, they are making us worse at being alone and worse at being together.

Ten years into the smartphone experiment, we may be reaching a tipping point. Buoyed by mounting evidence and a growing chorus of tech-world jeremiahs, smartphone users are beginning to recognize the downside of the convenient little mini-computer we keep pressed against our thigh or cradled in our palm, not to mention buzzing on our bedside table while we sleep.

Nowhere is the dawning awareness of the problem with smartphones more acute than in the California idylls that created them. Last year, ex-employees of Google, Apple and Facebook, including former top executives, began raising the alarm about smartphones and social media apps, warning especially of their effects on children.

Chris Marcellino, who helped develop the iPhone’s push notifications at Apple, told The Guardian last fall that smartphones hook people using the same neural pathways as gambling and drugs.

Sean Parker, ex-president of Facebook, recently admitted that the world-bestriding social media platform was designed to hook users with spurts of dopamine, a complicated neurotransmitter released when the brain expects a reward or accrues fresh knowledge. “You’re exploiting a vulnerability in human psychology,” he said. “[The inventors] understood this, consciously, and we did it anyway.”

Peddling this addiction made Mr. Parker and his tech-world colleagues absurdly rich. Facebook is now valued at a little more than half a trillion dollars. Global revenue from smartphone sales reached $435-billion (U.S.).

Now, some of the early executives of these tech firms look on their success as tainted.

“I feel tremendous guilt,” said Chamath Palihapitiya, former vice-president of user growth at Facebook, in a public talk in November. “I think we all knew in the back of our minds… something bad could happen.

“The short-term, dopamine-driven feedback loops that we have created are destroying how society works,” he went on gravely, before a hushed audience at Stanford business school. “It is eroding the core foundations of how people behave.”

None of the Bay Area whistle-blowers have been louder than Tristan Harris, a former star product manager at Google. He has spent the past several years of his life telling people to use less of the technologies he helped create through a non-profit called Time Well Spent, which aims to raise awareness among consumers about the dangers of the attention economy, and pressure the tech world to design its products more ethically. Judging by the momentum his movement is suddenly building – he receives hundreds of requests for speaking engagements a month – his message is being heard.

Policy makers and government leaders are among those listening. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau met with Mr. Harris at the Global Progress Summit in Montreal last September. The PM’s office wouldn’t provide details of the session, but if the federal government is considering restrictions on cellphone use, it wouldn’t be alone. This fall, France plans to ban mobile phones from primary and secondary schools, including between classes and during lunch breaks. “We must come up with a way of protecting pupils from loss of concentration via screens and phones,” said French education minister Jean-Michel Blanquer.

Business leaders are grappling with the issue, too. In a recent blog post, Bank of England analyst Dan Nixon argues that the distraction wrought by smartphones may be hurting productivity. It takes office workers an average of 25 minutes to get back on task after an interruption, he notes, while workers who are habitually interrupted by e-mail become likelier to “self-interrupt” with little procrastination breaks.

The TD Centre in downtown Toronto was channelling that business case against smartphones when it placed a coaxing poster in its lobby recently. “Disconnect to reconnect,” the poster read. “Put your phone down and be present.”

Yes, people are always put off by the strange power of new technologies. Socrates thought writing would melt the brains of Athenian youths by undermining their ability to memorize. Erasmus cursed the “swarm of new books” plaguing post-Gutenberg Europe. In its infancy, TV was derided as a “vast wasteland.”

But while previous generations may have cried wolf about new media, “it’s different this time,” Mr. Harris says. Unlike TVs and desktop computers, which are typically relegated to a den or home office, smartphones go with us everywhere. And they know us. The stories that pop up in your iPhone newsfeed and your social media apps are selected by algorithms to grab your eye.

Smartphones are “literally using the power of billion-dollar computers to figure out what to feed you,” Mr. Harris said. That’s why you can’t look away.

Socrates was wrong about writing and Erasmus was wrong about books. But after all, the boy who cried wolf was eaten in the end. And in smartphones, our brains may have finally met their match.

“It’s Homo sapiens minds against the most powerful supercomputers and billions of dollars …. It’s like bringing a knife to a space laser fight,” Mr. Harris said. “We’re going to look back and say, ‘Why on earth did we do this?'”

If we have lost control over our relationship with smartphones, it is by design. In fact, the business model of the devices demands it. Because most popular websites and apps don’t charge for access, the internet is financially sustained by eyeballs. That is, the longer and more often you spend staring at Facebook or Google, the more money they can charge advertisers.

To ensure that our eyes remain firmly glued to our screens, our smartphones – and the digital worlds they connect us to – internet giants have become little virtuosos of persuasion, cajoling us into checking them again and again – and for longer than we intend. Average users look at their phones about 150 times a day, according to some estimates, and about twice as often as they think they do, according to a 2015 study by British psychologists. .

Add it all up and North American users spend somewhere between three and five hours a day looking at their smartphones. As the New York University marketing professor Adam Alter points out, that means over the course of an average lifetime, most of us will spend about seven years immersed in our portable computers.

These companies have persuaded us to give over so much of our lives by exploiting a handful of human frailties. One of them is called novelty bias. It means our brains are suckers for the new. As the McGill neuroscientist Daniel Levitin explains, we’re wired this way to survive. In the infancy of our species, novelty bias kept us alert to dubious red berries and the growls of sabre-toothed tigers. But now it makes us twig helplessly to Facebook notifications and the buzz of incoming e-mail. That’s why social media apps nag you to turn notifications on. They know that once the icons start flashing onto your lock screen, you won’t be able to ignore them. It’s also why Facebook switched the colour of its notifications from a mild blue to attention-grabbing red.

App designers know that nagging works. In Persuasive Technology, one of the most quietly influential books to come out of Silicon Valley in the past two decades, the Stanford psychologist B.J. Fogg predicted that computers could and would take massive advantage of our susceptibility to prodding. “People get tired of saying no; everyone has a moment of weakness when it’s easier to comply than to resist,” he wrote. Published in 2002, Prof. Fogg’s book now seems eerily prescient.

The makers of smartphone apps rightly believe that part of the reason we’re so curious about those notifications is that people are desperately insecure and crave positive feedback with a kneejerk desperation. Matt Mayberry, who works at a California startup called Dopamine Labs, says it’s common knowledge in the industry that Instagram exploits this craving by strategically withholding “likes” from certain users. If the photo-sharing app decides you need to use the service more often, it’ll show only a fraction of the likes you’ve received on a given post at first, hoping you’ll be disappointed with your haul and check back again in a minute or two. “They’re tying in to your greatest insecurities,” Mr. Mayberry said.

Some of the mental quirks smartphones exploit are obvious, others counterintuitive. The principle of “variable rewards” falls into the second camp. Discovered by the psychologist B.F. Skinner and his acolytes in a series of experiments on rats and pigeons, it predicts that creatures are likelier to seek out a reward if they aren’t sure how often it will be doled out. Pigeons, for example, were found to peck a button for food more frequently if the food was dispensed inconsistently rather than reliably each time, the Columbia University law professor Tim Wu recounts in his recent book The Attention Merchants. So it is with social media apps: Though four out of five Facebook posts may be inane, the “bottomless,” automatically refreshing feed always promises a good quip or bit of telling gossip just below the threshold of the screen, accessible with the rhythmic flick of thumb on glass. Likewise the hungry need to check email with every inbox buzz.

Apple has made a point of presenting the dopamine dispensers of the mobile internet in the most alluring possible package, one that people would want to and be able to use non-stop – even behind the wheel of a car. Weeks before the iPhone’s launch, Apple gave out devices for senior staff to test in the real world. One engineer took the prototype on a test run to make sure it wasn’t overly difficult to text and drive with, according to tech journalist Brian Merchant, who wrote a history of the iPhone .

The phone’s most seductive quality was its screen. Throughout the iPhone’s development, Mr. Jobs fought to proceed without a keyboard, making the screen larger and more immersive. As the product was about to ship , he slammed on the brakes and demanded the case recede infinitesimally so the screen could be made larger still. This was a jarring innovation. Time magazine’s technology writer Lev Grossman was one of the first people outside Apple to see the iPhone, when he was sent to Cupertino, Calif., for a preview.

The screen’s unique power to absorb attention quickly became clear, though. In his first piece about the iPhone after its launch, Mr. Grossman observed, “There’s a powerful illusion that you’re physically handling data with your fingers.”

Though Mr. Grossman gave the iPhone some of its earliest rave reviews, that power to absorb that once seemed so dazzling, has come to trouble him. He now says the device has done more harm than good.

“We still haven’t understood or accepted how completely smartphones have distorted our daily lives and our social lives, and just our relationships with ourselves and with the reality around us,” he said. “We are divorced from ourselves and from the world – those relationships are now routed through our phones.”

On some level, we know that smartphones are designed to be addictive. The way we talk about them is steeped in the language of dependence, albeit playfully: the CrackBerry, the Instagram fix, the Angry Bird binge.

But the best minds who have studied these devices are saying it’s not really a joke. Consider the effect smartphones have on our ability to focus. In 2015, Microsoft Canada published a report indicating that the average human attention span had shrunk from 12 to eight seconds between 2000 and 2013. The finding was widely reported at the time and elicited some shock – for about eight seconds.

But John Ratey, an associate professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and an expert on attention-deficit disorder, said the problem is actually getting worse. “We’re not developing the attention muscles in our brain nearly as much as we used to,” he said. In fact, Prof. Ratey has noticed a convergence between his ADD patients and the rest of the world. The symptoms of people with ADD and people with smartphones are “absolutely the same,” he said.

A recent study of Chinese middle schoolers found something similar. Among more than 7,000 students, mobile phone ownership was found to be “significantly associated” with levels of inattention seen in people with attention-deficit disorder.

Maybe studies like these have gotten so little attention because we already know, vaguely, that smartphones dent concentration – how could a buzzing, flashing computer in our pocket have any other effect? But people tend to treat attention span like some discrete mental faculty, such as skill at arithmetic, that is nice to have but that plenty of folks manage fine without.

Valuable as it is, attention is also easy to squander. When taking in information, our minds are terrible at discerning between the significant and the trivial. So if we’re trying to work out a dense mental problem in our heads and our phone pings, we will pay attention to the ping automatically and stop focusing on the mental problem. That weak attentional filter is a bigger shortcoming in the smartphone era than ever before.

The average American in 2007 was absorbing the equivalent of 174 newspapers a day, via sources as wide-ranging as TV, texting and the internet – five times the amount of information they took in about two decades earlier .

In the smartphone era, that figure can only have grown. Our brains just aren’t built for the geysers of information our devices train at them. Inevitably, we end up paying attention to all kinds of things that aren’t valuable or interesting, just because they flash up on our iPhone screens.

“Our attentional systems evolved over tens of thousands of years when the world was much slower,” Dr. Levitin explained in an interview.

All that distraction adds up to a loss of raw brain power. Workers at a British company who multitasked on electronic media – a decent proxy for frequent smartphone use – were found in a 2014 study to lose about the same quantity of IQ as people who had smoked cannabis or lost a night’s sleep.

Even people who are disciplined about their smartphone use feel the effect.

The devices exert such a magnetic pull on our minds that just the effort of resisting the temptation to look at them seems to take a toll on our mental performance. That’s what Adrian Ward and his colleagues at the University of Texas business school found in an experiment last year. They had three groups of people take a test that required their full concentration. One group had their phones face down on the table, one had them in their bags or pockets and the last group left them in another room. None of the test-takers were allowed to check their devices during the test. But even so, the closer at hand the phones were, the worse the groups performed.

“It’s [one] of these things that’s pretty crazy and yet comports pretty well with how life feels,” Prof. Ward said.

Some people might be willing to trade 10 IQ points for the pleasures of their smartphone – especially the social pleasures. We’ve never been so capable of constant communication with others and for extroverts, that should be a blessing.

But 10 years into this age of connectedness, we have learned something troubling: Being connected to everyone all the time makes us less attentive to the people we care about most. Nowhere is the alienating power of smartphones more troubling than in the relationship between parents and children. Put simply, smartphones are making mothers and fathers pay less attention to their kids and it could be causing emotional harm. Lactation consultants in Canada and the United States have begun noticing the prevalence of women texting and scrolling through their phones while they breastfeed, breaking valuable eye contact with their baby.

“It is a whole new phenomenon,” said Attie Sandink, a breastfeeding educator based in Burlington, Ont. “It has on occasion become quite problematic.”

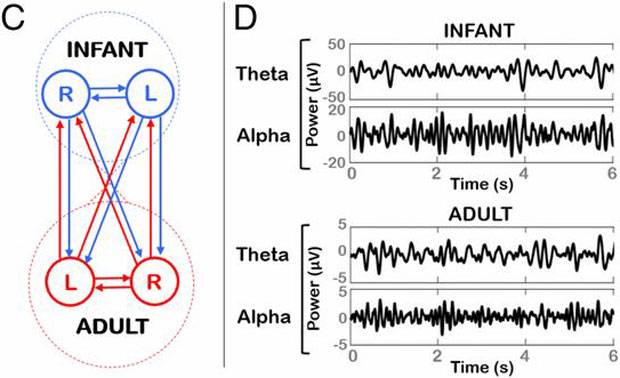

Researchers at Cambridge University showed recently that eye contact synchronizes the brainwaves of infant and parent, which helps with communication and learning. Meeting each other’s gaze, Ms. Sandink says, amounts to “a silent language between the baby and the mom.” That doesn’t mean breastfeeding mothers need to lock eyes with their children 24 hours a day. But while Ms. Sandink emphasizes that she isn’t trying to shame women, she worries that texting moms may be missing out on vital bonding time with their babies.

“While texting or communicating on their cellphones, do mothers possibly miss some of their [infants’] feeding cues or behavioural cues? Is the mother losing the hormonal interaction or interplay that baby signals to her?” Ms. Sandink said in an e-mail. “These are important questions to ask.”

Maybe it’s best for children to learn young that their parents frequently find their phone more absorbing than them, because they will learn sooner or later. Catherine Steiner-Adair, a clinical psychologist and research associate in psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, interviewed 1,000 kids between the ages of 4 and 18 for her 2013 book The Big Disconnect. Many of them said they no longer run to the door to greet their parents because the adults are so often on their phones when they get home.

And it gets worse once they’re through the door. One of the smartphone’s terrible, mysterious powers, from a child’s perspective, is its ability “to pull you away instantly, anywhere, anytime,” Dr. Steiner-Adair writes. Because what’s happening on the smartphone screen is inscrutable to others, parents often seem to have simply gotten sucked into another dimension, leaving their kid behind. “To children, the feeling is often one of endless frustration, fatigue and loss.”

The digital drift affecting families shows up in national statistics. The Center for the Digital Future, an American think tank, found that between 2006 and 2011, the average number of hours American families spent together per month dropped by nearly a third, from 26 to about 18.

Distracted parents may even be putting their children at risk of physical harm, Dr. Steiner-Adair says. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control found a 12-per-cent spike in injuries to children under 5 between 2007 and 2010, after a long decline. The years coincide with the crash of the American economy, but also with the infancy of the iPhone .

If there’s a silver lining to all of this grim evidence, it’s that the wages of smartphone addiction are beginning to take hold in people’s minds. When Dr. Steiner-Adair gives public talks, as she did in Maryland recently, parents often commiserate with her afterward.

“They all say roughly, ‘That was terrific and terrifying. We’re changing our family’s MO as of today,'” she said. “Just about everyone knows there’s something terribly wrong.”

She’s not the only person to notice the beginning of a turning point in the way people relate to their mobile computers. Just recently, Prof. Wu was thinking of taking out a smartphone in his daughter’s preschool class to play a song when he realized it would be taboo, given growing concerns about kids’ screen time – like “taking out a toy gun.”

“So it spreads,” he said. “It’s like a norm.”

Prof. Wu’s right: The belief that smartphones can be socially and mentally harmful – and that their overuse should be stigmatized – is spreading into the culture in little ways. A recent Dilbert cartoon showed a doctor looking wide-eyed at a medical chart and telling his patient, “The MRI shows that your brain has been hijacked by dopamine pirates.” (When the patient asks, “Are you writing me a prescription,” the doctor replies, “No, I’m buying stock in those companies.”)

Even comedian Will Ferrell has joined the struggle. In a series of videos produced by Common Sense Media for the U.S. nonprofit’s #DeviceFreeDinner campaign this fall, the actor plays a smartphone-addled father whose family tries to lure him away from his screen. In one clip, Mr. Ferrell’s wife and kids persuade him to place his phone in a basket on the dinner table, but the father finds a loophole: “As long as it’s in the basket, though, I can technically still touch it, right?” he says, his finger creeping toward the screen of his imprisoned device.

A culture shift is happening in Silicon Valley too. An ex-Google product manager, Ben Tauber, recently became executive director of the rejuvenated Esalen Institute, a former hippie hotel in California where techies have taken to visiting for unplugged weekends of soul searching about the plugged-in world they’ve created.

Still, for all the hints of change in the air, Mr. Harris remains on high alert. Billions of people continue to be distracted and turned away from loved ones thanks to their smartphones. And untold billions of dollars, wielded by some of the world’s biggest companies, are devoted to keeping it that way. In fact, every financial incentive spurring the flanks of these firms is telling them to make smartphones more compulsively usable and therefore more damaging, not less.

Mr. Harris and other smartphone skeptics are starting to hatch ideas, some more plausible than others, about how the devices might be made less toxic. Imagine, Mr. Harris said, if Facebook’s app delivered all your notifications at once, at a given time of day, like the mail. Prof. Wu, meanwhile, has suggested that tech companies should develop a phone designed to protect users’ attention and time. He would pay double, he said.

The trouble with reforming these products, of course, is that the versions we have now are kind of amazing – fun to use and wildly convenient. That’s why they’re so addictive.

The lesson we’re slowly beginning to learn, though, is that they’re not a harmless vice. Used the way we currently use them, smartphones keep us from being our best selves. The world is starting to make up its mind about whether it’s worth it and whether the sugary hits of digital pleasure justify being worse, both alone and together.

We need to make up our minds soon, Mr. Harris said.

“I worry that we’re not going to get this fast enough.”